Design docs are a fundamental tool for communicating software design decisions–but communicating things is hard and so is writing design docs. Time for an overly detailed exploration into what would happen if one wrote a design doc for design docs.

May 19th, 2015

Status: Draft

Authors: Malte Ubl

Note: While this post continues to be independently useful, I have published a more approachable write-up about Google's use of design docs in Design Docs at Google

Context and scope #

Software design is an important element of software engineering in which, after we established the requirements of the product or system we are building, we make plans and decisions how to best implement those requirements in software.

This document describes how a design document is used to facilitate the process of coming to an agreement on a software design and to document it for current and future implementers, maintainers and other stakeholders of the software.

Goals #

Document the software design.

Clarify the problem being solved.

Act as discussion platform to further refine the design.

Explain the reasoning behind those decisions and tradeoffs made in that decision.

List alternative designs and why they were not chosen.

Support future maintainers and other interested parties in understanding why the original design was chosen.

Non-goals #

Establish non-technical requirements of the software.

Be independently understandable by a person with no background in the software (but links should guide to documentation that covers missing parts).

Act as user documentation for the product or system.

Suitable to document non-software-designs such as the design of a design doc.

Overview #

Our core design idea is that we use a document to informally describe the software design. This extra step before the implementation is chosen, because it has proven inefficient to evolve early software design in terms of fully working implementations. For similar reasons maintainers who try to understand an existing software system often struggle to understand the fundamental design decisions just by looking at the source code.

The design doc starts with explaining the objective of the software design, how it fits into the wider landscape and why the problem at hand was sufficiently complex to warrant a design document. Explicitly listing goals and non-goals is done to encourage thinking about them.

The document then continues with a short overview of the design without describing all the details. This overview is followed by the detailed design section that contains the bulk of the content describing why the design was chosen and what the software design is.

Several sections on cross cutting concerns such as privacy and security directly address how the design relates to them.

We finish by quickly describing what alternatives were considered and why they were not chosen.

Design documents are designed to be an efficient design documentation and discussion platform. As such the writer may take great liberties in the actual content and form to best express the design.

Detailed design #

The process of designing software should ideally have the following properties:

Draws on the experience of experts of the topic matter from within and around the team.

Is flexible to changing requirements of the software.

Produces a guideline for the initial implementation.

Produces accurate documentation of the software design behind the actually implemented software.

Produces a design that is implementable within the given constraints such as time and resources.

Quickly establishes that a chosen design is viable.

Quickly establishes that a chosen design is not viable and then produces a viable design.

Reduces the risk that a design is not viable.

Produces simple designs.

If applicable comes to the conclusion that an existing solution exists and no design is necessary.

While some of the requirements in this (incomplete) list may seem redundant, some cannot be achieved at the same time.

The most direct way to show whether a system can be implemented is to implement it, but that may take too long to quickly establish what the right design is and requirements may have changed by the time the viability of the design under the old requirements was proven.

In this trade-off-space the design doc plays a vital role by being easy to collaborate on and informal, yet relatively exhaustive and updateable over time:

By using modern collaborative software, such as Google Docs, experts from the team and beyond can collaborate on the final document.

Being informal allows the content and form to be tailored to the design issue at hand making it an efficient way to document designs.

The same informality reduces the “cost of change”.

The software design toolbox contains things such as “the proof of concept”, “the micro benchmark” and “the white board discussion”. While it is beyond the scope of this design doc to explain all of them they should be considered as part of the software design process. E.g. pointing to a proof of concept can be a great way in a design doc to establish the viability of the design.

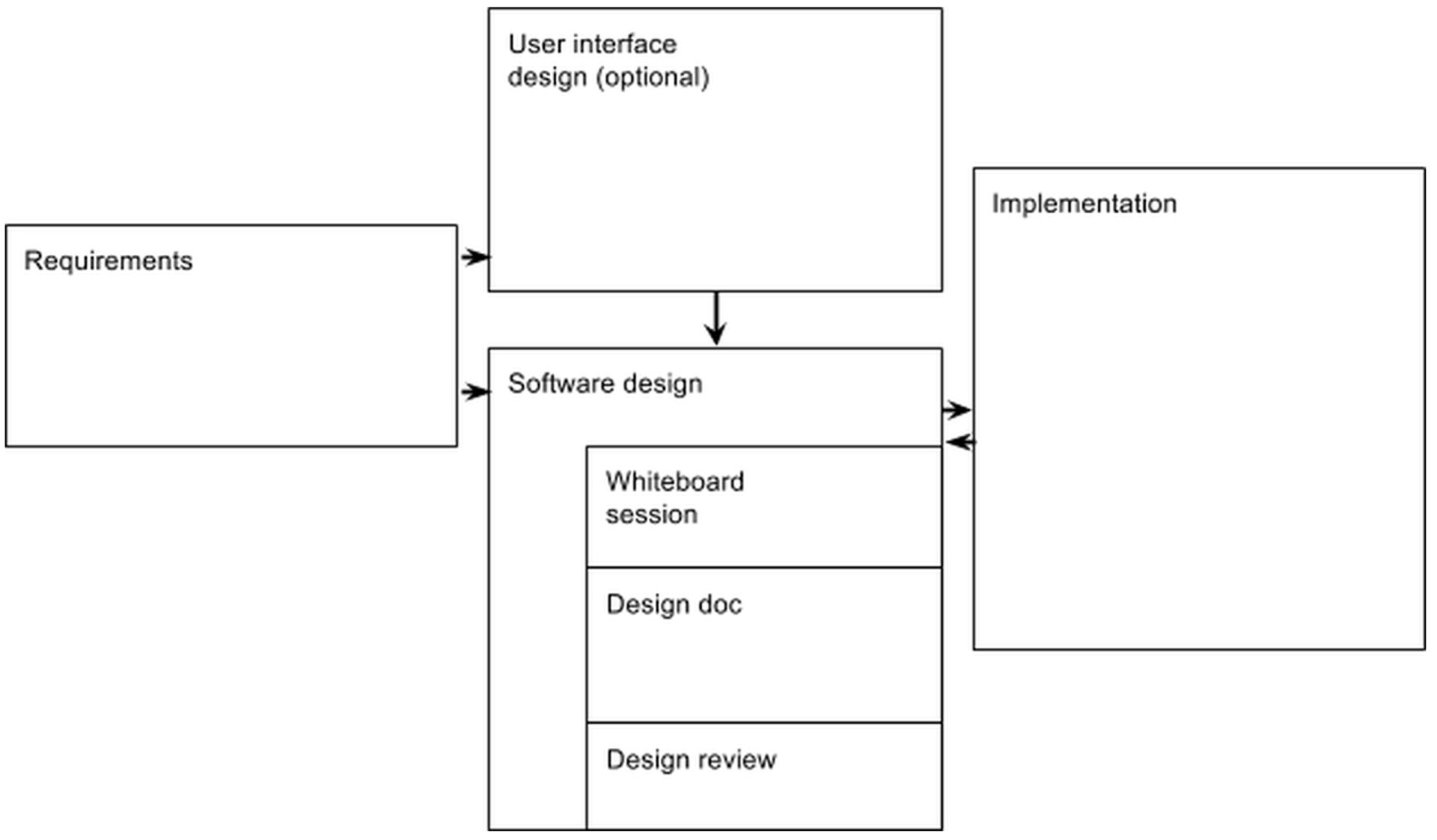

Relationship to other systems #

The design doc is written as part of the development of the software design. It gets informed and refined through other elements of software design such as whiteboard sessions and design reviews.

Software design is primarily driven by the project requirements and if applicable by the user interface design. The requirements, independent of how they are expressed, define what a piece of software should do while the design establishes how that is achieved and why that design was chosen. The design then informs the implementation and the implementation feeds back into the design (through updates of the design when it confronts with reality).

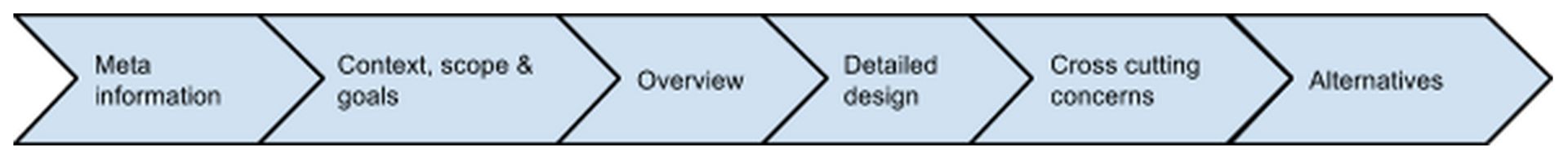

Structure #

The structure of a design doc is chosen, so that a reader can efficiently and effectively dive into the subject matter. The document starts out relatively high level and then dives deeper into the details of the design.

This “funnel” is chosen so readers

can quickly evaluate the context, scope and goals of the design and get a basic understanding of the design.

and can then choose to read the entire document.

Meta information #

Design docs should always have a title and immediately state their authors as primary contacts and a last updated date. Stating the status is helpful for setting expectations for the reader as to the completeness and definiteness of the document. Useful states are:

enum[ ] DesignDocState { UNKNOWN = 0; INCOHERENT_RAMBLING = 1; DRAFT = 2; FINAL = 3; IMPLEMENTED = 4; OBSOLETE = 5; };

(The above code snippet was inserted to illustrate the point further down that copy pasting irrelevant code snippets is not a great idea.)

Context, scope & goals #

The document should first establish the context and scope of the design. This may be done across multiple or a single paragraph. This section should include bullet point lists of “Goals” and “Non-goals” for three reasons:

It is an efficient way for the reader to establish what the design tries to achieve and what it doesn’t want to achieve.

It can be used to evaluate whether the detailed design establishes how those goals are achieved.

It forces the authors to actually make decisions about the scope.

Overview #

Next the document gives an overview of the design. This helps readers gain an understanding of the overall approach, which will make it much easier to evaluate how the details relate to the design. It is important to realize that the design doc should not build up tension when being read from start to the end. Quite the opposite, information is given as fast as possible and the structure should aim to avoid putting related information too far apart.

Detailed design #

This section explains the design, its trade offs and consequences as appropriate. The concrete contents are greatly determined by what is being designed and will vary widely between various types of systems, APIs, front ends, etc. The authors are explicitly empowered to choose a form that best fits their design.

See “Level of detail” below for guidance as to what should determine the contents of the detailed design section.

Cross cutting concerns #

There may be one or multiple chapters that talk about specific concerns from their specific point of view. While the entire design should have them in mind the dedicated chapters ensure that they are addressed and highlight how the design applies to them. Examples for such concerns are privacy, security, scalability and monitoring.

Alternatives considered #

This section is a fixed part of the document structure as it forces the authors to think about what alternatives would have been available to achieve the goals of the design. Alternatives may be other possible designs or the use of an existing system that does almost what is needed, the purchase of a standard software or to do nothing at all.

Level of detail #

As stated before a design doc should be an efficient platform for design discussion and documentation. The longer the document gets the harder it becomes to consume and change. The document should thus be as short as possible and as long as necessary.

No definite guidance can be given when a document is too detailed, but there are some signs when this is the case:

Specification of APIs that are not vital to the design.

Copy pasted source code that is only partially relevant to the design.

Raw data.

Bullet point lists that contain an extra item for no good reason beside meta referentiality.

Given the design doc a software engineer who either has existing experience in the subject matter or is willing to invest to get that experience should be able to implement the design doc.

In a similar manner a “reasonable software engineer” with experience in the subject matter should be able to follow why the design was chosen even if they do not agree with the conclusion.

The design document itself is not responsible to give any reader independent of their prior experience full context into the subject matter but it should provide links that enable the reader to establish the full context necessary to follow the rest of the doc.

Lifecycle #

Document creation #

Early in the lifecycle of a design doc major changes are more likely than later in the project when the design is more settled. Early iterations of the document should thus be as lightweight as possible so that changes are quick and the author’s resistance to change it minimized.

Techniques such as whiteboarding and sketching out chapters with bullet point lists may be employed in early phases of the doc.

While the document itself is informal, initial setup can be sped up through the use of templates or by the time proven technique of copy pasting the last design doc one has written. The usage of these templates helps ensure a minimum level of coverage and reduces boilerplate.

Canary rollout #

When the document has stabilized it is advisable to first share it with a small set of canary readers. These will often be peers who participated in early whiteboard sessions and design discussions. By incorporating their feedback into the design doc we ensure that no major questions are unaddressed and ensure general soundness of the design before circulating it with a wider audience.

Rollout #

At this time the document is shared with the wider team and other stakeholders. Readers are encouraged to ask questions and make suggestions via inline comments and authors reply. If warranted the document should be updated to address the feedback.

Eventually the design is declared final. Often this happens informally signaled by the fact that people start implementing the design.

Security and privacy considerations #

The design doc has dedicated sections for security and privacy considerations and other such cross cutting concerns if applicable to ensure that they are sufficiently addressed.

Alternatives considered #

Meet in front of a whiteboard, draw stuff on it, take a photo.

It is great when this is sufficient to document a design, but often systems are too complex to be expressed through a single whiteboarding session and people who did not themselves take part in the discussion may be missing context.

Having said that, whiteboarding sessions are a great start to flesh out the major points of a design in a lightweight process before diving in to actually write it down.Agile Scrum KISS™, just winging it.

Doing the simplest thing that could possibly work is generally a great idea but it stops being fun when that includes a lot of boilerplate or in aggregate becomes so complex that everyone loses track what is going on. If the simplest thing that could work is still complex a design doc may help document that simplest thing.Verbal design review

Design reviews are another way to discuss a design and spread knowledge about it. It can be a great addition to every design doc but is insufficient to serve as long term evolving documentation of a project’s design.

Published